The expressions swear like a trooper and swear like a sailor are so common as to be cliché. But why do we swear ‘like a trooper’ or ‘like a sailor’? And what else do we swear like, idiomatically, in English and other languages?

Troopers and sailors

Swearing has long been identified with the military, source of so much slang, ribald chants, tribal insults, and other forms of strong language. Profanity would come into its own in war, aiding both bonding and catharsis: ‘an easement to the much besieged spirit’, as Ashley Montagu put it.

So routine was swearing in WWI that to omit it carried real force. In his 1930 book Songs and Slang of the British Soldier: 1914–1918, John Brophy writes, ‘If a sergeant said, “Get your ––––ing rifles!” it was understood as a matter of routine. But if he said “Get your rifles!” there was an immediate implication of urgency and danger.’

We can assume that fucking is the censored word. The spread of fuck through war is described in Ruth Wajnryb’s Expletive Deleted (2005):

If the ideals of the French Revolution were spread on the bayonets of Napoleon’s soldiers, then it might be said that the worldwide penchant for fuck was spread by American soldiers on the battlefields of World War II . . .

The spread of fuck and other swears in military contexts is depicted in much 20thC literature (perhaps most famously Norman Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead) and film: Full Metal Jacket apotheosizes epithet-laden profanity in memorable, and sometimes cartoonish, rituals of dominance and abuse.

So when I looked up swear like a [X] in a bunch of language corpora, alongside trooper I was not surprised to find soldier, sergeant, and Vietnam veteran. More on those corpus findings below.

More sweary even than troopers are sailors. Sailor is the most common object in the idiom, and sailor-adjacent bargeman, docker, longshoreman, marine, navvy, pirate, stevedore, and wharfie do regular duty. After filming Inside Llewyn Davis, Ethan Coen said it was ‘fun to see Carey [Mulligan] swear like a stevedore’.

Grammarphobia says trooper and sailor top the list probably because these groups ‘had reputations for boorish language and behavior when the two phrases showed up’ – swears like a trooper in the 18thC, sailor in the 19thC. It dates the idiom to 1730 and traces how the associations became established.

That these formulas are now entrenched is evidenced in the data, where sailor and trooper dominate heavily. But dozens of variants also occur, and even the more clichéd forms are often modified to make things more interesting.

Corpus data

I used wild-card searches to look up the phrases swear like a, swears like a, swearing like a, and swore like a, and the equivalents with curse and cuss, in Mark Davies’s language corpora.

I disregarded examples like swears like a Christian, …French Canadian, …gentleman, …girl twice her age, and …kid that are descriptive rather than emphatic and idiomatic. Swears like an [X] results were sparse and also generally fell into this category.

Here’s a rough summary of the main findings, with corpus names along the top. Note the profusion of shipping-related occupations:

![Table showing the frequency of [X] in the phrase 'swear/curse/cuss like a [X] in four language corpora: NOW, iWeb, COCA, and COHA. Listed down the left, in decreasing order of frequency, are: sailor, trooper, trucker, pirate, motherfucker, longshoreman, navvy, rapper, madman, stevedore, fishwife, and docker. Numbers for the first 5 are as follows. Sailor: 288, 181, 62, 12. Trooper: 87, 74, 4, 14. Trucker: 24, 18, 4, 3. Pirate: 5, 6, 1, 7. The rest all total 8 to 10 across the four corpora.](https://stronglang.files.wordpress.com/2022/12/stan-carey-strong-language-swear-like-a-x-in-4-language-corpora.jpg)

* trooper includes trouper; trucker includes truck driver; motherfucker includes mother, mofo, and mo’fo; navvy includes navvie; rapper includes rap artist, rap star, gangsta rapper, and hip hop star; madman includes maniac; docker includes dockworker.

[Caveats: I counted quickly, so I can’t swear I didn’t fuck up a little, and some results appear in more than one corpus. But errors and duplicates should be fairly negligible.]

The table shows a clear top three: sailor, trooper, and trucker. But in the historical corpus COHA (1820–2019), trooper has a slight edge and pirate jumps into third place.

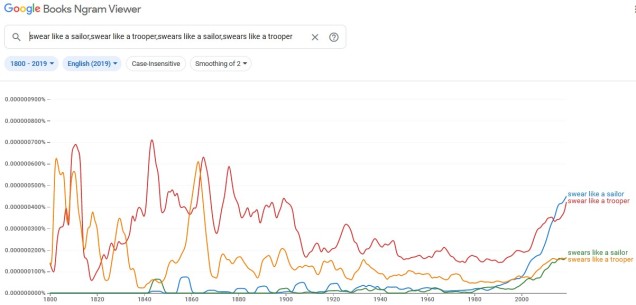

The Google Books Ngram Viewer is less accurate, less balanced, and less powerful than the corpora above, but it does give quick, approximate curves of usage; here, trooper dominates the scene before sailor catches up:

Here are some highlights from Davies’s corpora:

Sweary sailors in the NOW corpus (16.4 billion words from newspapers/magazines, 2010–2022) include a happy sailor, filthy sailor, murderous sailor, sailor in Greek, sailor on shore leave, sailor’s parrot, sailor with Tourette’s, shipwrecked drunken sailor, 15-year-old sailor in jail, and ‘a soldier, sailor and merchant seaman rolled into one’.

There’s a traffic-stuck trucker and a truck driver/politician (alternatives, I presume, not a moonlighting situation). There’s a demented stevedore, a battalion of fishwives, a pirate with toothache, three marines, two banshees, two soldiers (one wounded), and ‘a foul-mouthed trooper stubbing their toe on a slang dictionary’.

Among NOW’s hapax legomena for the phrase are a *%$#*, biker, cabbie, chippie, construction worker, dirty old man, drunk, fish, fookin’ champ, frat boy, heathen, house on fire, lascar, line cook, millworker, oilfield worker, PPL cricketer, residential oaf, [Guy] Ritchie movie, sergeant, squaddie, and Tarantino film.

More elaborately there’s ‘a chef who has just burnt his fingers in the soufflé’, ‘a gang member from the projects in LA’, ‘a middle-schooler on XBOX Live’, ‘a mother hen whose chick had been snatched by a kite’, and ‘a tennis player’s fiancee in a half-time team-talk’.

The less formal iWeb corpus (14 billion words from ~95,000 websites, 2017) has a similar distribution. Examples that reinforce the emphasis or allay the cliché include ‘a whole field of troopers’, a ‘schooner full of drunken navvies’, and a ‘J.B. Hunt graduate’ (for a trucker, I guess).

It also has a couple of wharfies and chefs (one of these a line cook), a bargee, big ass Baptist, bitch, coster-monger, cutter, drunk, drunken bushwhacker, drunken Irishman, lumberjack, mariachi, merchant seaman, metho-fuelled hobo, satin [sic] possessed freak, seadog, and teenager.

COCA (Corpus of Contemporary American English: 1 billion words from various genres, 1990–2019) has a sailor on crack and a drunken sailor on the last day of leave. Joining them are a crack dealer, habitual drunkard, ‘a Hells Angel or a high school junior’, lumberjack, truck-stop waitress, stinging wasp, and surly barmaid.

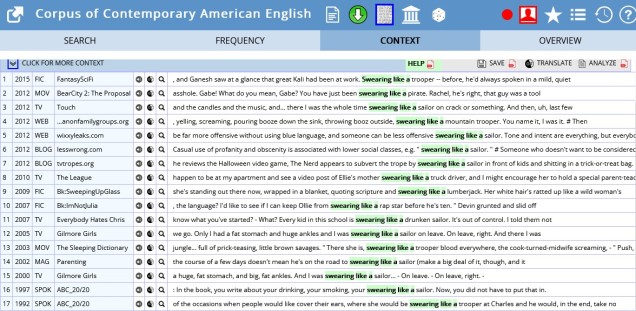

This selection of swearing like a [X] in COCA gives a flavour of the contexts:

We can also graph the genres the phrase tends to appear in: mostly fiction, magazines, and TV/movies. Frequencies are low, though, so the short bar in the spoken register is perhaps less surprising than it would otherwise be:

![Bar chart showing the frequency of '[swear] like a [X]' across genres. In decreasing order: fiction, TV/movies, magazines, web, news, blogs, spoken, academic. Beside it is a smaller bar graph showing frequency across recent 5-year periods, peaking in 2005-2009.](https://stronglang.files.wordpress.com/2022/12/coca-swear-like-a-genres.jpg?w=636)

Swearers in COHA (Corpus of Historical American English: 475 million words from various genres, 1820–2019) are mostly from fiction. Hapaxes include buccaneer, demon, drill instructor, Fourth Ward politician, mule driver, mule skinner, sheriff, surly barmaid (the same one), and taxi driver.

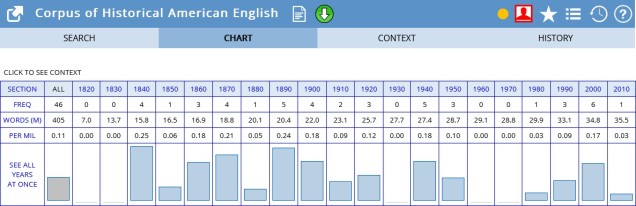

Here’s when they occur, from the 1820s to the early 21st century. The frequencies are too low to draw any solid conclusions:

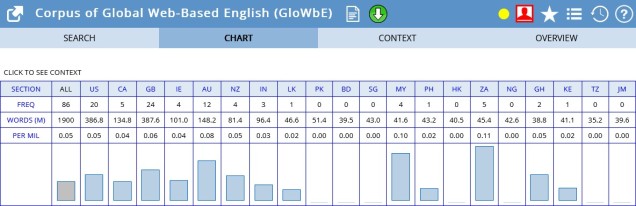

This graph from GloWbE, a corpus of 1.9 billion words from websites in 2012–13, gives a rough indication of the relative occurrence of swear like a [X] in 20 countries where English is used. Again, the hits are too few to read much into it, but note the peaks in South Africa, Malaysia, and Australia:

Results in other corpora were still more scant. The Movie Corpus adds a stable boy and ‘a cowhand on payday’. The TV Corpus has a porn star, a trooper with a PhD, a tuppeny whore, and a lumberjack who hacked off a leg. The British National Corpus and Corpus of American Soap Operas have a handful of the usual suspects.

Stereotypes

For all the great variety, there’s a predictable reliance on stereotypes of class and gender: the majority are working-class men doing physical labour. Many are drunk. Exceptions like mother hen, barmaid, and lord prove the rule. (Lord predates the corpora, showing up in Thomas Elyot’s The Governour (1531): ‘They wyll say that he that swereth depe, swereth like a lorde.’)

The perception that swearing is indulged only by people in lower socioeconomic classes is really a perception by the more genteel middle classes, who are more likely to avoid swearing: perhaps to distance themselves from poorer people or because they don’t believe the upper classes swear. But they do.

British monarchs were infamous for strong language, including Henry VIII and Elizabeth I (who was said to swear ‘like a man’). Even today, Prince William casually uses the word bollocking. The venerable game of flyting, a kind of insult contest, reached its zenith among aristocrats and court poets in 16thC Scotland. In Norse myth it was practised by the gods. And Geoffrey Hughes observes, in his Encyclopedia of Swearing:

Those British prime ministers noted for using coarse or strong language in public derive almost entirely from noble families, such as William Pitt and Charles James Fox from an earlier era, the last being Sir Winston Churchill.

The predominance of men in the data reflects both perceptions and norms of recent centuries. Women were excluded from many of the sweary jobs. Even so, Ruth Wajnryb writes that historically ‘there is ample evidence that men swore more than women’.1 The social mores that produced that imbalance have progressed a bit, at least when it comes to women saying fuck in British English.

Which brings us to fishwife, easily the most popular female variant in the expression. Traditionally it often collocated with Billingsgate, a fish market in London. Writes Jonathon Green in Sounds and Furies: ‘The eponymy of the place name and the alleged foulness of the language used by those who worked there is first recorded in 1676 and flourished as a stereotype for three centuries.’

Today the stereotype feels archaic, though Hughes in his Encyclopedia lists fishwife alongside trooper and tinker among the ‘bywords of swearing’.2 Swearing like a fishmonger is not unheard of but was never proverbial, at least in English; in swearing like a fishwife we find gender and class intersecting in the gibe.

Other languages

Huge thanks to comrades on Signal and Mastodon for responding to my query about analogous expressions in other languages. I’ve compiled their data and anecdata in brute fashion below. The Mastodon thread has nuances of sense and usage that I’ve left out, so click through if you want more of that:

Croatian: swear like a coach driver

Czech: swear like a sailor, tiler/paver, pagan (klít jako pohan), starling (nadává jak špaček)

Danish: swear like a Turk (at bande som en tyrk), sailor (sømand), docker (havnearbejder)

Dutch: curse like a docker (vloeken als een dokwerker/bootwerker), tinker (ketellapper), trooper (dragonder), fishwife (viswijf), heretic (ketter), boilermaker

Estonian: swear like a coachman (voorimees)

Finnish: swear like a sailor (kiroilla kuin merimies), Turk (turkkilainen), lumberjack (tukkijätkä)

French (Canada/Quebec): swear like a log driver (jurer comme un draveur), cart driver (sacrer comme un charretier), lumberjack (bûcheron) [note the Catholic verb sacrer]

French (France): swear like a cart driver (jurer comme un charretier), pagan (païen), fishwife (une poissonnière)

German (Austria): swear like a washerwoman (fluchen wie ein Waschweib)

German (Germany): swear like a brewer’s drayman (fluchen wie ein Bierkutscher), tinker (Kesselflicker), sailor (Seemann), broom-maker (Bürstenbinder), farmhand or mercenary (Landsknecht), coach driver (Kutscher), cab driver (Droschkenkutscher), reed bunting (schimpfen wie ein Rohrspatz) [not an occupation, granted, but there’s no way I was going to omit the reed bunting]

Greek: swear like a trucker (βρίζω σαν νταλικέρης)

Hungarian: swear like a cart driver (kocsis)

Irish: swear like the devil (mallachtú ar nós an diabhail)

Italian: swear like a Turk (bestemmiare come un turco), docker (uno scaricatore di porto), cart driver (un carrettiere), fishwife/fishmonger (pescivendola)

Norwegian: swear like a docker/stevedore (banne som en bryggesjauer)

Polish: swear like a cobbler/shoemaker (kląć jak szewc)

Portuguese (Brazil): swear more than a sailor (xinga mais que um marinheiro / fala mais palavrão que um marinheiro), talk like a docker (fala como um estivador). And regionally ‘curse like a carioca’

Portuguese (Portugal): swear like a cavalry sergeant (sargento de cavalaria)

Romanian: swear like a cab (coach) driver

Russian: swear like a cobbler/shoemaker (материться как сапожник), swear like a horse driver (ругаться как извозчик), foreman

Slovak: swear like a cart driver (nadávať ako kočiš), pagan (pohan) [or with the old-fashioned verb kliať]

Slovenian: swear like a coachman (preklinja kot kočijaž/fijakar/furman), sailor (mornar)

Spanish (Mexico): swear like a female greengrocer (tener boca de verdulera), truck driver (camionero), talk like a cart driver (hablar como carretonero); there’s also the saying ‘You’re so vulgar you’d make a construction worker blush’ (Eres tan vulgar que harías sonrojar a un albañil)

Spanish (Spain): speak like a female greengrocer (hablar como una verdulera)

Swedish: swear like a sailor (sjöman), broom-maker (svär som en borstbindare)

As well as the obvious parallels with English, there are interesting differences and patterns. Turks and especially cart drivers are popular in many languages. I’m not sure if there’s a significant difference between a cart driver and a coachman, etc., so I haven’t collapsed these.

The sole heathen I found in NOW is echoed in Dutch heretic (ketter), French pagan (païen), and Czech pagan (pohan). Fishwife reappears in the Netherlands (viswijf), France (poissonnière), and Italy (pescivendola). Some obsolete occupations remain, forming fossil idioms; in other cases updates can be imagined, like drayman to trucker.

As well as swearing like a cart driver, Hungarian also has an expression that means ‘plucking the saints from heaven’ to refer to swearing a lot. The same idiom occurs in Puerto Rican Spanish (bajar los santos del cielo) and presumably elsewhere.

I may add to the list if more examples come in. Feel free to add notes, corrections, other examples, or your own favourites in a comment. The list so far is pretty Indo-European-heavy, so examples from other languages would be particularly welcome.

*

1 Bear in mind that there’s evidence of men doing lots of things more than women simply because that’s the kind of evidence that was considered worth leaving, gathering, and studying. But a proper treatment of the sexist double standards applied to historiography and to women swearing is beyond the scope of this post.

2 A tinker is someone who mends pots and other kitchen utensils. In Ireland, where I’m from, the word is a slur for Irish Travellers.

Thank you. I will start using “swear like a rapper’s parrot” from now on.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I like it. I’m going to try out “swear like a degenerate starling”.

LikeLike

“Swear like a sailor’s/rapper’s wife” is good, too.

LikeLike

The military is great for coming up with curse word acronyms like snafu and fubar.

LikeLike

Yes, it’s a great source of slang. Snafu and fubar seem to have emerged in WWII, and both appeared briefly in an old post on sweary abbreviations. A more recent post, on visual swears in film, featured the Fu-Bar in Z Nation.

LikeLike

A quick search in French shows “like a rag picker” (pattier). It may be Swiss in origin, and “pattier” shows up on a couple of sites as a Savoyard regionalism.

I also found “like a Templar” and wonder how old it is, the Templars having been disbanded in the early 14th C – although long after that they were a byword for all sorts of bad behavior, e.g. “drink like a Templar”. Both seem to be little used since the 19th C.

LikeLike

Thanks for looking into the phrase in French – those are both interesting versions of it. The Templar example does raise the question of when it emerged.

LikeLike

Rather interestingly, standard French does not appear to use “comme un chiffonnier,” as we would call a rag picker today. Sites where “jurer comme un pattier” is discussed explain that it means the same as “jurer comme un charretier”.

Also, it occurs to me that the Templars are not just exemplars of bad behavior but also are soldiers, albeit cross-bearing ones. Oh, and speaking of the military link, I came across “jurer comme un grenadier”.

LikeLike

It’s curious to see how these idioms rub up against contemporary experience. I’d guess that most people who say swear like a trooper don’t generally use the word trooper in any other context, and some might not even have a mental image to go with it; it’s just a set phrase, one that centuries ago had more ‘solidity’ because its referent was more familiar. And different linguistic and social factors will inform whether a given version of the idiom survives its object’s obsolescence.

LikeLike

The Spanish results seemed interesting, but not quite comparable, so I went and did some corpus digging myself and got 22 examples from CREA/CORDE

Part of the problem is that most Spanish dialects use constructions that are not quite equivalent to swear. There are a bunch of relevant verbs with that syntax (blasfemar ‘to blaspheme’, jurar ‘to swear’, maldecir ‘to curse’), but they are all dated or literary these days. So most of the results I got were from literature. But with that caveat, we have some interesting patterns:

many of the comparisons were religious in nature: como un demonio ‘like a demon’, como un hereje ‘like a heretic’, como un moro ‘like a Moor’, como un réprobo ‘like a reprobate’… but also como pontífices ‘like Popes’! One of the most common similes is of this kind: como un condenado ‘like a damned soul’ (×4)

others are simply about being loud and obnoxious: como un furioso or un obseso ‘like someone furious’ or ‘obsessed’

professional similes are not that far from the English ones: I found como un marinero ‘like a sailor’, como un mulero ‘like a muleteer’, como un soldado ‘like a soldier’ (×2), and an ironic como señoritos ‘like lordlings’, alongside what’s clearly the most canonical version: como un carretero ‘like a carter or coach driver’ (×5)

Pérez Galdós seems to have shared my thoughts about carters being sweary par excellence in Spanish: this quote explicitly plays with the convention

“Trabajadores de todas clases y carreteros que blasfemaban como señoritos (valga la inversión de los términos de este símil), transitaban por el puente y el camino, cruzándose con arrieros de Fuenlabrada y hortelanos de Leganés o Moraleja” (Pérez Galdós, B. 2002 [1878]. La familia de León Roch. Universidad de Alicante)

My own Rioplatense Spanish uses different constructions for this, mostly tener la boca sucia ‘to have a foul mouth’. I’ll have to dig around other corpora to see if I can find data about those

LikeLike

This is really helpful, Alon, thank you. I’ve never learned any form of Spanish, but I figured there must be many more variants of the phrase out there than I heard about through my query online. The religious cluster is especially interesting. Some versions use hablar but are evidently the same idiom, so that may be worth exploring if you didn’t already.

LikeLike

In our family it has always been “swear like a longshoreman,” which isn’t surprising when I consider that my grandfather, father and several great-uncles worked on the docks in Brooklyn in the mid-20th century.

I am proud to carry on their tradition (of swearing, not working on the docks).

LikeLike

And rightly so.

LikeLike

A more modern translation of the original than “proves” would be “the exception tests the rule”. It is not a get-out clause, it demands a more rigorous rule that includes all cases. There are, after all, eight quotations in the OED for “swear like a lord” from 1531 to 1932.

Worth mentioning that tinkers are almost as early as lords:

1611 R. Cotgrave Dict. French & Eng. Tongues Il iure comme vn Abbé [etc.], [he swears] like a Tinker, say we. (Swears like an Abbot in the French, hilariously)

1630 T. Dekker Second Pt. Honest Whore iv. i. 207 [He] swore like a dozen of drunken Tinkers.

I found some others in the OED that you don’t seem to have included:

1598 W. Shakespeare Henry IV, Pt. 1 iii. i. 243 You sweare like a comfit-makers wife.

In this case Hotspur is pointing out to Lady Percy that the oath “in good sooth” that she used is too sweet and dainty, like a sweet-maker’s wife might use. “Swear me, Kate, like a lady as thou art, A good mouth-filling oath, and leave ‘in sooth’, And such protest of pepper-gingerbread, To velvet-guards and Sunday-citizens.”

1594 W. Shakespeare Henry VI, Pt. 2 i. i. 186 Oft haue I seene this haughtie Cardinall..Sweare..like a Ruffin.

I found that was badly edited, it should be unrelated to your article:

Sweare, and forsweare himselfe, and braue it out,

More like a Ruffin then a man of Church”

Ruffin in this case being a demon or devil rather than a type of fish, I think. Later editions have “Ruffian” or “ruffian”.

1663 Proposal to use no Conscience 6 We swear like Gentlemen of Rank, Curse, Damn, Sink.

1701 G. Farquhar Sir Harry Wildair ii. i. 14 Drink like a Fish, and swear like a Devil. (George Farquhar was an Irish writer, so may have derived it from the Irish example given above, or coined it and given it to Ireland).

a1734 R. North Lives of Norths II. 57 His infirmities were passion, in which he would swear like a cutter[, and the indulging himself in wine.] (cutter – “One over-ready to resort to weapons; a bully, bravo; also, a cutthroat, highway-robber. Obsolete.” The person being described was Lawrence Hyde, Lord Rochester, who surely swore like a lord? North was paradoxically born in Suffolk.)

Slightly off-topic, I was reminded of the phrase “swear like blue blazes”:

1858 S. A. Hammett Piney Woods Tavern 37 And the two Jacobs swore like blue blazes agin him.

“Blue blazes” apparently meant “the flames of hell”. This was, presumably, from someone familiar with the colour of the flames of sulphur/brimstone. If you are not, seek out a videos of the burning sulphur at the Kawah Ijen volcano.

LikeLike

Thanks for listing these, Patrick. I consulted the OED but confined my discussion to the corpus findings mentioned, mostly for reasons of space. So it’s helpful to have these added here. I’m inclined to think that ‘swearing like the devil’ predated Farquhar, given how integral the devil is in Irish (and hence Irish English) vernacular; P. W. Joyce devoted a whole chapter of English As We Speak It in Ireland (1910) to the subject.

LikeLike